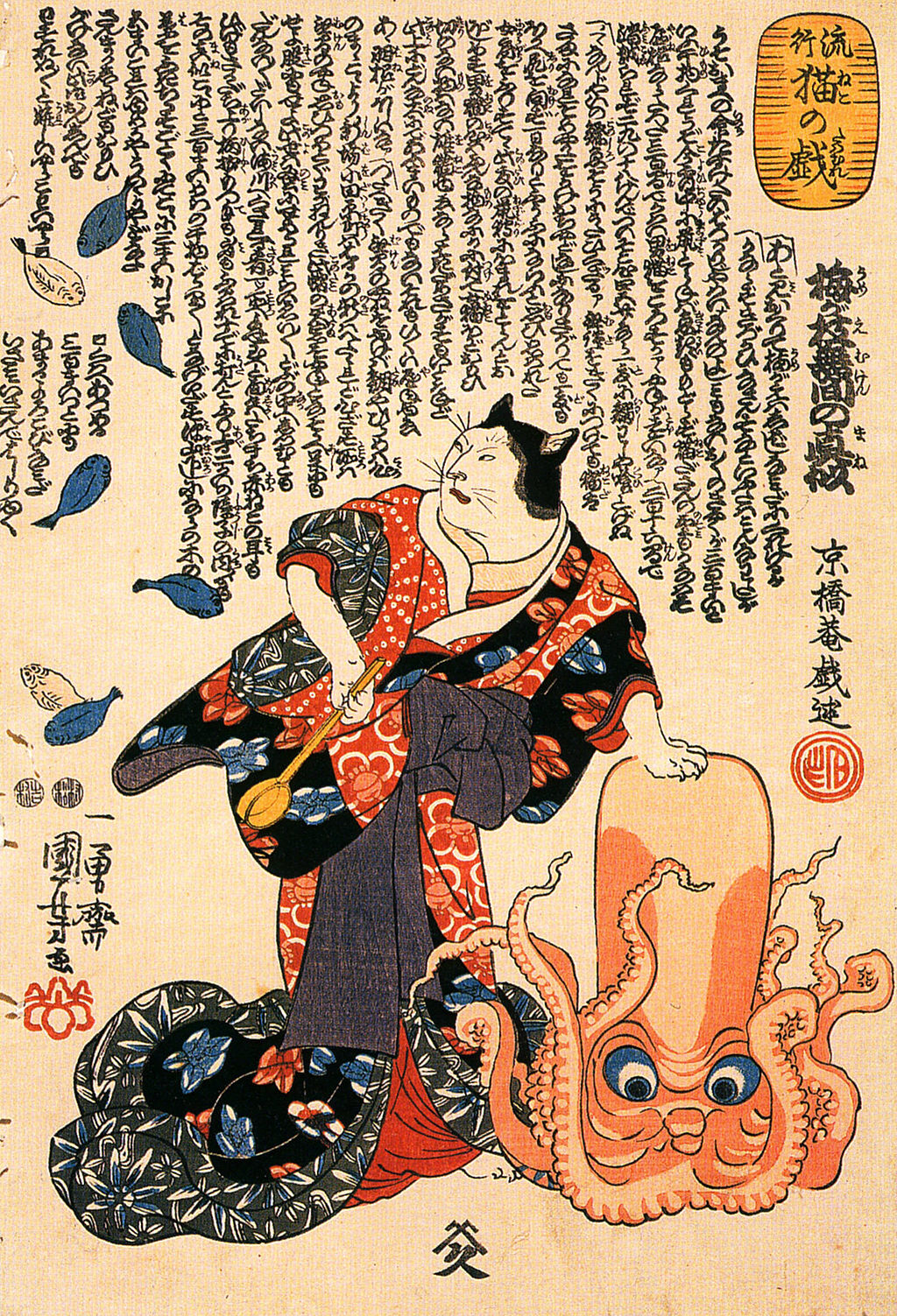

Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s “Cat Dressed as a Woman” features, unsurprisingly – a cat dressed as a woman, playfully tapping (or maybe bopping) an octopus on the head. Though tongue-in-cheek, the scene evokes the same energy as a kabuki drama or a fairy tale: transformations, hidden identities, and a dash of comedic absurdity. On the surface, it might have little to do with modern courtship in Japan, but let’s not underestimate how old folktales and even older felines can point us toward new insights.

The tale we’re interested in is sometimes called The Mouse Turned into a Maid, an ancient story of Indian origin that migrated across cultures, eventually finding its way into Japan. Its central plot: A humble father (or a holy man, depending on the version) tries to secure the most powerful suitor imaginable for his daughter, who was originally a mouse. First, he petitions the sun. When the sun says the cloud is mightier, he tries the cloud, then the wind, then the mountain, everyone keeps pointing him elsewhere. Finally, he’s back to where he started: the mouse. After all, like marries like. Nature’s pecking order only goes so far.

In the Japanese variant, the father’s quest for an all-powerful match is dashed when he realizes that even towering mountains yield to little rodents that munch and burrow in hidden places. Philosophically, it’s a reminder to find a partner on equal terms rather than chasing hierarchical illusions. Which brings us to modern-day Japan, where illusions about marriage and the refusal of it are in the cultural spotlight.

In today’s Japan, a growing number of women are opting out of the traditional marriage track altogether. Some prefer focusing on their careers; others are postponing marriage until they find a genuinely equal partner. A few simply enjoy the freedom of living solo, building a life that revolves around personal goals, friendships, and, well, fun. They might be inadvertently re-enacting the lesson from The Mouse Turned into a Maid: that “finding the most powerful suitor” isn’t always the best blueprint for happiness.

It’s easy to see parallels between the old father’s comedic quest and the all-too-real cultural pressures to marry “the perfect catch.” Could it be that some modern Japanese women have decided to step off that treadmill? In a society that historically valued rigid hierarchies; think feudal lords, samurai codes, and elaborate courtship rituals, modern women are increasingly saying: “I’m not your mouse-maid, and I don’t want the sun, the moon, or the wind. I’m good on my own.”

This might sound rebellious in a land famed for harmonious living, but Japanese history is also full of creative acts of subversion. Kuniyoshi’s cat might reflect that same spirit. Instead of quietly purring, it’s dressed to the nines and tapping an octopus, presumably unconcerned about what the “right” behavior for a cat should be. Likewise, women choosing singledom are forging their own paths, tapping the cultural octopus on the head, so to speak.

Over centuries, the fable of the mouse-maid has been told in India, the Middle East, Europe, and East Asia, sometimes highlighting social mobility, sometimes cautioning against marrying above one’s station, and sometimes emphasizing that nature trumps nurture. In Japan, its comedic edge is softened by a sense of respectful acceptance for the cosmic order: everything has its place, but that place might not look like your parents’ ideal wedding photo.

Modern Japanese women who choose not to marry could be seen as embodying that acceptance in a brand-new way. They’re not clamoring for the “most powerful suitor” or any suitor at all. They’ve taken a page from the fable, realizing that no external label—whether social, familial, or cultural can define one’s worth.

In the end, the old father in the Japanese fable goes in circles only to discover that love, like identity, thrives where it naturally belongs. For some, that means fulfilling the traditional path; for others, it might mean ignoring the script entirely. And for still others, it might mean working to rewrite cultural expectations—like cats who refuse to stay cats and giant mice who dare to dream.

Kuniyoshi’s cat in a woman’s kimono playfully reminds us that transformation, whether literal or metaphorical, has long been part of Japan’s narrative tapestry. And today, as more women choose to remain single, they’re effectively rewriting an ancient fable: no father, no suitor, just one’s own terms.

Painting by Utagawa Kuniyoshi 1798 – 1861

Author’s Note

Before you judge the cat for tapping the octopus or the mouse for preferring a mouse-husband, take a moment to think about how we all engage in transformations, some big and some small, when we’re looking for (or avoiding) a partner. Sometimes it’s best to stay true to who you are, whether that means standing tall on your own or finding a fellow rodent to share your cheese.

Because in the end, if a mouse can become a bride, a cat can dress as a woman, and women themselves can say “no thanks” to marriage, maybe the greatest power is simply having a choice.

Leave a Reply to Tammy Cancel reply