If you’ve ever gotten lost looking for someone’s house in Japan, congratulations. You’ve taken part in a time-honored national pastime known as “navigating the address system.” Unlike in many Western countries, where streets have names and houses have clear numbers in neat little rows, Japan prefers a more poetic approach. Addresses are more like cryptic regional codes, and street names are optional at best, nonexistent at worst. That’s where the hyousatsu comes in the humble household nameplate.

In Japan, slapping your family name next to the front door is not just a nice touch, it’s essential. Since multiple houses can share the same address block, postal workers and delivery people rely on these signs to know who lives where. Imagine trying to deliver sushi in a neighborhood where every building is called 3-5-22. It’s like a logic puzzle wrapped in polite confusion. Western addresses might say “123 Maple Lane,” but in Japan it’s more like “Area 3, Block 5, Building 22 – good luck.” The nameplate is the final clue, the Rosetta Stone of the Japanese postal system.

But there’s more to it than just logistics. Putting up a hyousatsu is also a cultural signal. It says, “We live here. Permanently. Probably.” It fosters a sense of community and trust. It’s like a friendly wave to your neighbors, only made of engraved wood or stainless steel. While in the West you might have a cute doormat that says “Welcome-ish,” in Japan you get a sleek sign that announces your legal surname and spiritual commitment to the plot of land it rests on.

Speaking of spiritual, nameplates weren’t always this practical. Historically, they evolved from household talismans meant to protect the home from misfortune. Think of them as a mix between a doorbell and a protective charm. In some regions, it was believed that stealing a nameplate could unleash contagious magic, which is possibly the most specific crime deterrent in history. It also makes you think twice before pulling a prank on your neighbor’s mailbox.

Some modern homeowners opt for stylized fonts or use Roman letters to keep a little mystery, part privacy, part design choice. Others go full custom with little animal icons or seasonal motifs. It’s like a business card for your house, except with less networking and more spiritual symbolism.

So the next time you visit a Japanese neighborhood and spot a tidy nameplate by the door, remember you’re seeing more than a label. It’s history, tradition, postal coordination, and possibly supernatural defense, all carefully attached to the wall with double-sided tape or tiny nails. In the West, we hang wreaths. In Japan, we hang identity.

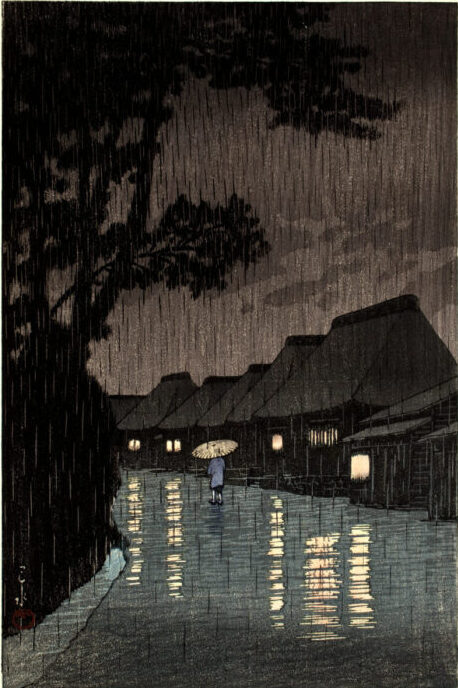

Rain in Maekawa Soshu by Hasui Kawase

Author’s Note

There’s something quietly poetic about a culture that trusts its postal system to find a house using invisible roads and spiritual signage. As someone who once delivered pizzas in a grid-based suburb where every street name was a tree and every house number was legible from space, I find Japan’s approach to home identification both baffling and beautiful. It’s less “drop it at the door” and more “enter the narrative.” Maybe that’s the charm — that even the smallest sign can say, “You’re home.” Or at least, “You’re not far off.” Also, if anyone knows where I can get a hyousatsu with a cat and a moon on it, please forward the link.

Leave a Reply