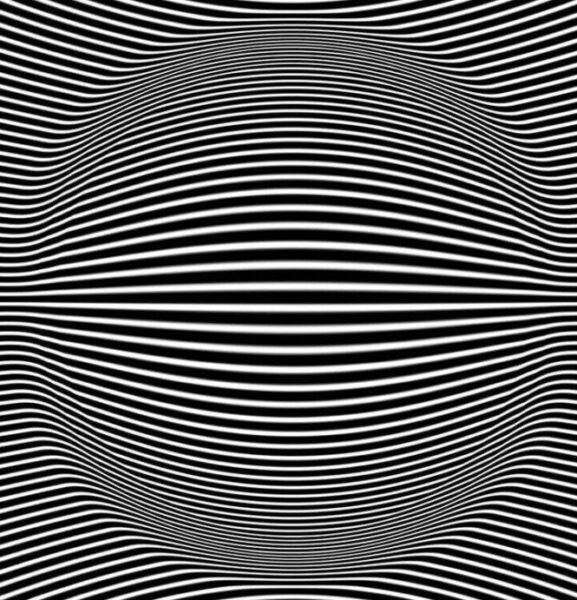

There’s something quietly mesmerizing about this image. A grid of white lines on black, undulating as if pressed from behind by a round force, almost like a sphere is trying to emerge through fabric. Yet there’s nothing there. It’s flat. An illusion. And still, we can’t help but feel the depth. We see a shape. Our minds insist on form, even where there is none. This is not just a trick of the eye—it’s a gateway to deeper reflection. Within this visual distortion lies a world of quiet philosophies, particularly from Japan, that help us understand what we’re really looking at, and perhaps, what we’re really looking for.

At the heart of this experience is Yuugen (幽玄) – a Japanese concept that gestures toward subtle, profound beauty and mystery. There’s no literal object here, yet something stirs. The swelling of the lines hints at a presence we can’t quite touch or name. Yuugen doesn’t demand explanation. It suggests. It whispers. In this image, it is the soft echo of a form we imagine more than we see. Western aesthetics might relate this to the sublime, the overwhelming awe found in the vast and unknowable. But Yuugen is quieter. It’s not about grandeur. It’s about the way a shadow plays on the wall, the way a moment opens and then dissolves before we can name it.

As our eyes trace the curves, we begin to enter a different kind of awareness, one free from overthinking. This is Mushin (無心), the “no-mind” state valued in Zen practice. To view the image is to fall into a kind of visual meditation. The lines guide us, gently, and we follow without effort. There’s no need to interpret. The experience itself is enough. In Western terms, we might call this flow, a term popularized by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi – a state of full immersion, where time softens and the self momentarily disappears. This image invites that state. It doesn’t ask you to solve it. It simply lets you be in it.

Look a little longer, and you’ll notice something else: it’s not perfectly symmetrical. The distortion of the lines isn’t mirrored exactly. There’s a human quality to it, a slight irregularity. And that’s where Wabi-Sabi (侘寂) enters. This Japanese aesthetic embraces imperfection and impermanence. The image, though seemingly digital and exact, reveals tiny asymmetries that make it feel organic, alive, even. In contrast, much of Western classical art pursues symmetry, harmony, and perfection. But Wabi-Sabi reminds us that beauty can be found in what is slightly off, in what is worn, in what carries the soft fingerprint of time or error.

There’s also a fleeting quality to the illusion. The first time you see the depth, it’s powerful. But once your mind registers the trick, the sensation begins to fade. And yet you return, hoping to feel that impression again. That quiet ache, that gentle sense of loss, is Mono no Aware (物の哀れ) – an awareness of impermanence and the bittersweet beauty of transience. The image never really changes, but you do, in each moment of seeing. It’s a reminder that perception is not fixed. And that even the smallest experiences, a glance, a ripple, a line can carry the weight of meaning, if we let them.

Though there is no literal circle in this image, it holds the presence of one. The bulging form suggests a sphere, a hidden roundness just beneath the surface. In this, we can feel the influence of Enso (円相) – the Zen circle drawn in one breath, representing enlightenment, the void, and the beauty of imperfection. An Enso is often left open, suggesting that completeness does not require closure. Here, the illusion of a circle is formed not by drawing one, but by bending the space around it. This is not a thing made visible, it is a thing made known through suggestion, like the empty center of a mandala, or a thought left unspoken but deeply felt.

So what are we really looking at?

We’re looking at lines. But we’re also looking at the mind’s need to find form, to fill in gaps, to make meaning from pattern. This image, though abstract, becomes a kind of visual koan – a Zen riddle not meant to be answered, but experienced. It doesn’t tell you what to see. It reveals how you see.

In this way, it reflects not only Japanese philosophy, but a universal truth: that perception is not passive. It is creative. Our eyes don’t just receive. They interpret, imagine, remember. And in that act, beauty arises, not from what is, but from what we bring to it.

The illusion of depth is a metaphor. It asks us to consider the layers of our own perception. How often do we mistake the appearance of form for truth? How often do we fill in what’s missing, needing wholeness where there is only suggestion? And isn’t there something beautiful in that very act?

Art like this simple in structure, complex in experience, reminds us to slow down. To see, not just look. To feel, not just interpret. It invites us into a deeper way of being, one that recognizes the subtle, the fleeting, and the imperfect as essential parts of the whole.

Perhaps that’s the greatest illusion of all that depth is out there, beyond us. When in fact, it begins here, in the mind, in the quiet curve of a thought, in the space between lines.

Author’s Note

This piece began with a simple image, a ripple in a grid but the longer I looked the more I felt it looking back. Writing about it turned out to be an act of tracing shadows: thoughts I couldn’t quite name at first, only sense. Somewhere between Yuugen and Mushin, I realized the image wasn’t the subject at all. It was a mirror. A soft, silent one.

We often chase meaning through clarity, but some of the most profound things arrive not with answers, but with echoes. I hope this piece helps you notice the depth in the flatness, the curve in the stillness, and maybe even the presence in what isn’t there.

And if it doesn’t, that’s fine too. Some things are meant to be glanced at sideways.

Leave a Reply