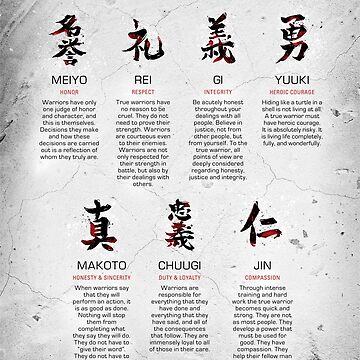

In 1900, Nitobe Inazō offered the world a vision of samurai ethics through Bushido: The Soul of Japan. He framed seven core virtues (rectitude, courage, benevolence, respect, honesty, honor, and loyalty) not simply as rules for warriors, but as principles for living with dignity and moral clarity. Doing what is right, standing brave in the face of fear, protecting others with kindness, speaking the truth, offering thoughtful respect, taking pride in righteousness, and holding fast to loyalty: these were distilled from centuries of practice into a guide that crossed both time and culture.

Yet before Nitobe, samurai ethics were neither codified nor universal. Emerging during the Kamakura period and evolving through the Edo era, ideals of honor, bravery, and fidelity varied by clan, context, and circumstance. Texts such as the Kōyō Gunkan, Hagakure, and the writings of Yamaga Sokō reflected overlapping themes: readiness to face death, moral duty, and Confucian virtues of propriety and responsibility. Zen, Shinto, and Confucian thought shaped these traditions, teaching warriors not only discipline of the body but also discipline of the mind. Law and custom guided conduct, yet practice was always local, lived, and contingent.

Nitobe’s contribution was clarity and synthesis. In a time when Japan was rapidly modernizing, adopting Western technologies, and opening itself to foreign influence, he sought to preserve an ethical identity while presenting it in terms accessible to the world beyond. It is striking to consider that the “ancient” code many associate with Japan is barely 120 years old, a product of late 19th-century intellectual diplomacy. Christian faith framed his lens, drawing parallels between samurai virtue and biblical ideals of justice, kindness, and self-sacrifice. His wife, Mary Elkinton Nitobe, brought a Quaker perspective emphasizing pacifism, simplicity, integrity, and equality. Together, they transformed scattered warrior codes into a moral vision that could speak universally, bridging cultures through ethical reflection.

Mary’s background in Philadelphia’s socially active Quaker Elkinton family equipped her for this work. Her upbringing emphasized moral reasoning, intellectual inquiry, and social reform. Meeting Nitobe in the mid-1880s, she honed her cross-cultural fluency, becoming not only a partner in life but also a collaborator in thought. Their marriage in 1891 was as much a fusion of ideas as of hearts, combining the discipline of samurai tradition with the introspective, moral, and egalitarian sensibilities of Quaker philosophy.

Nitobe’s admiration for Britain shaped his work further. He saw the United Kingdom as a model for order, governance, and moral authority in a modernizing world. He praised British colonial administration for its efficiency and “civilizing mission” and sought to adapt its principles in Japan’s governance of Korea and Taiwan. This admiration reinforced the chivalric parallels in Bushido, helping Western audiences recognize familiar virtues while positioning Japan as a modern, ethically minded nation among global powers.

The West, in turn, embraced Bushido with fascination. Emerging amid post-Sino-Japanese War Orientalism, it resonated with familiar Christian ideals of justice, benevolence, and loyalty, while romanticizing the samurai as noble and exotic. Films, literature, and martial arts culture reinforced this perception, often simplifying or overlooking historical realities. Scholars now note that Nitobe’s synthesis was both selective and aspirational, projecting Western ideals onto a diverse warrior class while omitting peasants, women, and the messy realities of political violence. While Nitobe envisioned Bushido as a bridge to the West, the idealized loyalty he described was later co-opted by domestic hardliners to fuel a more aggressive state nationalism, a tragic irony given Nitobe’s own commitment to international peace.

The Nitobes were not only authors but educators. In Sapporo, they ran the informal Enyū Yagakkō night school for working girls, while also supporting Tokyo Women’s Christian College, Tsuda College, and Keisen Women’s College. Nitobe’s own years at Sapporo Agricultural College, as student and later professor, were transformative. Inspired by William S. Clark’s exhortation, “Boys, be ambitious!”, he embraced Christianity and imagined bridges between East and West. Teaching economics, agronomy, and literature while advising local communities, he cultivated both intellect and insight. A health crisis in 1897 forced him into reflective isolation, during which he composed Bushido, turning personal struggle into a work with enduring global resonance. These experiences also influenced educational reforms, as his ideas about ethics, diligence, and civic responsibility permeated classrooms and curricula, shaping generations of students.

Bushido, as Nitobe presented it, is less a literal code than a dialogue between history, philosophy, and global imagination. It reflects the lived realities of a warrior class, the ethical frameworks of spiritual and intellectual mentors, and the cross-cultural lens of Nitobe and Mary. Understanding it fully means recognizing both the aspirations and the omissions: the selective framing, the idealized virtues, and the way these principles traveled from feudal Japan to international audiences, shaping perceptions, inspiring action, and prompting reflection across generations.

Author’s Note

Writing this article reminded me how ideals travel. Nitobe and Mary Elkinton Nitobe lived at the intersection of cultures, beliefs, and personal trials. Their vision of Bushido was shaped by samurai discipline, Christian faith, and Quaker ethics, yet also by the small, human contingencies of their lives: health crises, long nights of teaching, and reflective isolation. History is never tidy. Bushido is neither a strict manual nor a complete mirror of samurai life, but it tells a story of moral ambition, cross-cultural dialogue, and the human desire to reconcile ethics with action. For me, thinking through these journeys of virtue and interpretation was like walking alongside a distant past that still echoes in the present. I wrote this while sipping coffee that slowly went cold, which felt fitting for an article exploring enduring human ideals amid the passage of time.

Leave a Reply