Before Akira exploded onto the international stage with its kaleidoscopic violence and apocalyptic scale, there was Dōmu a tighter, darker psychic pressure cooker set in a single Japanese housing complex. Both works were written and illustrated by Katsuhiro Otomo, and while Akira became the icon, Dōmu was the whisper that preceded the scream. One is cosmic. The other is claustrophobic. But in both, the city is breaking and something old and terrible is leaking out of the cracks.

Dōmu (1980–1981) is a horror story told in the language of realism. The setting is uncomfortably familiar: a public housing complex, densely packed with lives stacked on top of one another. Murders are happening, unexplainable ones. The police are baffled. But Otomo wastes no time pointing to the real cause: an elderly man with psychic powers who has turned the building into his personal psychological playground. This isn’t science fiction as escape. It’s urban unease pushed to the limit.

What’s eerie in Dōmu is how normal everything seems until it doesn’t. The psychic violence erupts without warning, but never feels out of place. It’s as if the very structure of the building is complicit, like the oppressive architecture has absorbed every scream and sigh of its residents. This is a key Otomo signature: buildings matter. Cities are characters. And when they collapse, they do so with the weight of accumulated trauma.

Enter Akira (1982–1990), the loud, sprawling sibling. Where Dōmu is a locked-room mystery with psychic knives, Akirais a neon epic. Neo-Tokyo is both a rebirth and a warning, rebuilt after a psychic detonation that destroyed the original city. The same tension that hummed quietly in Dōmu what happens when repressed power finally erupts is now turned up to eleven.

Tetsuo, like the old man in Dōmu, is a latent psychic ticking time bomb. But instead of haunting a single complex, he tears through a metropolis. His transformation isn’t just physical. It’s ideological. He becomes a symptom of everything Otomo fears about unchecked potential in an unstable society: fascism, scientific hubris, and the myth of progress devouring its own children.

Despite the scale difference, the two stories rhyme. In both, children and the elderly carry psychic burdens the adult world can’t handle. In both, institutions fail police, scientists, governments. And in both, power isolates. The psychic isn’t a superhero. It’s an aberration. A curse disguised as evolution.

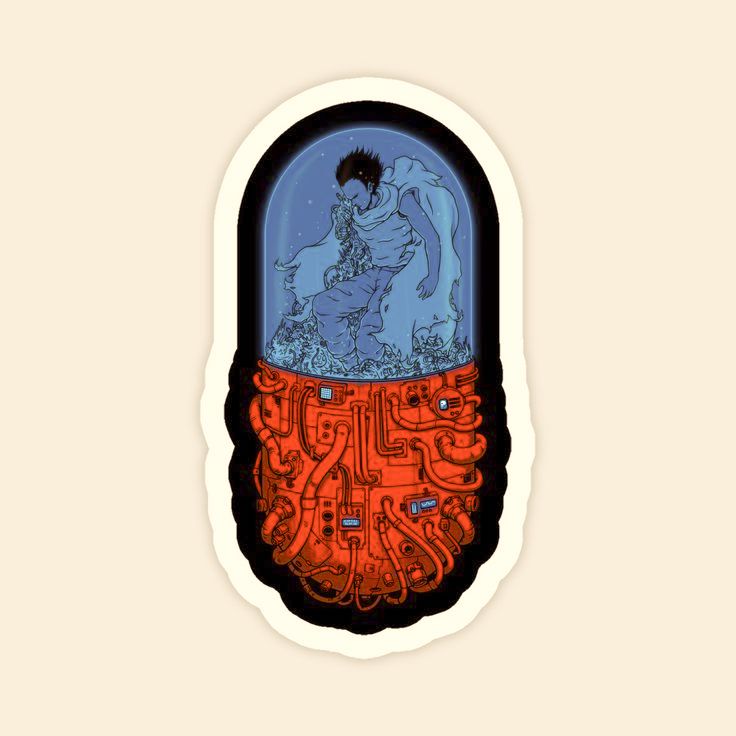

There’s also the shared obsession with the built environment. Otomo draws concrete like other artists draw skin. Every crack, every rusted pipe, every panel of urban entropy is lovingly rendered. In Dōmu, the building becomes a sealed ecosystem of fear. In Akira, the city becomes the laboratory, the battlefield, and the casualty. Technology doesn’t liberate. It magnifies the fallout.

Philosophically, both works tap into deep anxieties in postwar Japan about control, collapse, and the psychological residue of catastrophe. The psychic powers don’t represent hope. They’re more like karmic feedback. Humanity digs too deep, reaches too far, and the result isn’t enlightenment but obliteration. This is a very different trajectory than Western superhero narratives. There’s no “with great power comes great responsibility.” In Otomo’s world, great power comes with great ruin.

And yet, there’s something tender too. In Dōmu, a young girl with her own powers ultimately defeats the old man not through brute force, but through emotional steadiness. In Akira, the story ends not with victory but with transformation. The city is erased again. Something new begins. Not clean. Not resolved. But possible.

That’s the real pulse under Otomo’s concrete. Not redemption. Not revolution. But an unsettling hope, twitching under the rubble.

Author’s Note – 作者より一言

If your walls start making noises, don’t worry, it’s probably just the building developing psychic abilities. Happens in Otomo’s neighborhoods all the time.

アキラの叫びの前に、ドームのささやきがあった。

世界中に衝撃を与えた『アキラ』の万華鏡のような暴力と終末的スケールが爆発するよりずっと前 – その前にあったのが『童夢』だ。舞台はたった一つの団地。密閉空間でじわじわと高まる超能力の圧力鍋。どちらも大友克洋の作品だが、『アキラ』がアイコンとなったのに対し、『童夢』はその前に忍び寄る囁き声。ひとつは宇宙的。もうひとつは息苦しいほど密室的。そして、どちらの街も壊れ始めている。そこから滲み出すのは、古くて恐ろしい“何か”だ。

『童夢』(1980〜1981)は、リアリズムの言語で語られるホラーだ。舞台は見慣れた風景 – 日本の公団住宅。ぎゅうぎゅうに詰め込まれた生活が階層状に重なっている。だが、そこでは説明不能な殺人事件が続発。警察はお手上げ状態。しかし大友は時間を無駄にしない。犯人はすぐに明かされる- 超能力を持つ老人が、建物全体を自分の精神的遊び場にしていたのだ。これは“逃避”としてのSFじゃない。都市に潜む不安を限界まで引き延ばした作品だ。

恐ろしいのは、『童夢』の中で何もかもが“普通”に見えること。異常が日常に溶け込んでいる。突如として始まる超能力バトルが、なぜか違和感なく感じられるのは、団地そのものが共犯に見えるからだ。住人たちの叫びやため息を、建物が吸い込み続けてきたような圧迫感。これこそ大友作品の真骨頂 – 建物には意味があり、都市は人格を持つ。そしてそれが崩れるとき、積もり積もったトラウマの重みで崩壊する。

そして次に現れるのが、『アキラ』(1982〜1990)。『童夢』が閉じられた密室ミステリーなら、『アキラ』はネオンで光る壮大な叙事詩だ。ネオ東京は、かつての都市が“超能力による爆発”で吹き飛ばされた後に再建された、希望であり、警告でもある街。『童夢』で静かに鳴っていた「抑圧された力が暴走するとどうなるか」という不安が、ここでフルボリュームになる。

テツオは、『童夢』の老人のような存在だ。ただし、ひとつの団地を超えて、都市そのものを突き破る。彼の変化は身体的変異だけでなく、思想的な変質でもある。テツオは、制御されない“可能性”が暴走したときの恐怖の象徴だ。そこには、ファシズム、科学の傲慢、進歩という神話が自らを食いつぶす不吉な未来が重ねられている。

スケールは違えど、両者は呼応している。どちらでも、超能力という重荷を背負っているのは、子どもか老人。つまり、大人の世界が手に負えない存在だ。そしてどちらでも、制度は機能しない。警察も、科学者も、政府も。そして何より、力を持った者は孤独だ。超能力者はヒーローではない。進化の仮面をかぶった異常。呪いだ。

そして何より、大友作品には“建築”への執着がある。彼はコンクリートを、他の作家が肌を描くように描く。ひび割れた壁、錆びた配管、都市の崩壊が1コマ1コマに息づいている。『童夢』では建物自体が密封された恐怖の生態系となり、『アキラ』では都市が実験室であり、戦場であり、犠牲者となる。テクノロジーは解放ではなく、崩壊を拡大する道具だ。

思想的にも、この2作品は戦後日本が抱える深い不安――管理、崩壊、そして災厄の心的残滓――に触れている。ここで描かれる超能力は希望ではない。むしろカルマの逆流に近い。人類は掘りすぎ、求めすぎ、そしてその先に待つのは啓蒙ではなく、消滅だ。これは西洋的なヒーロー像とは全く異なる。「大いなる力には大いなる責任が伴う」なんて誰も言わない。大友の世界では、「大いなる力には、大いなる破滅がついてくる」。

……でも、ほんの少しだけ優しさもある。

作者より一言:

『童夢』では、少女が老人を打ち負かすのは力ではなく、心の安定によってだ。そして『アキラ』のラストに待つのは勝利ではない。変容だ。街はまたしても消され、新しい何かが始まる。綺麗でも、解決でもない。だが、“可能性”がある。

それこそが、大友のコンクリートの下でかすかに脈打っているもの――贖罪でも、革命でもない。不穏な希望。その残骸の中で、微かに震える「まだ終わってない」の感覚。

ご希望があれば、タイトルや見出しを追加したり、書籍紹介風に整えたりもできますよ。

Leave a Reply