Normalcy bias is that handy little glitch in our brains that makes us assume everything will always be fine, because it has been, right? It’s a cognitive bias where people underestimate the likelihood or impact of a disaster or crisis, believing that life will continue as usual simply because it always has in the past. This charming delusion causes us to ignore threat warnings, downplay red flags, and sometimes continue folding laundry while the kitchen fills with smoke.

It’s not that people are stupid (mostly). It’s just that the human brain prefers comfort over chaos. When the unimaginable knocks at the door, normalcy bias hands us a cup of tea and says, “Relax, it’s probably just the wind.” This is why 70 to 80 percent of people, during actual disasters, do something remarkably unhelpful like checking their email or wondering whether they left the oven on instead of evacuating.

You’ve seen it. People refusing to leave during hurricanes because “this one doesn’t feel serious,” or calmly sipping a latte during a fire alarm, confidently proclaiming, “It’s probably just a drill.” There’s a surreal comedy in how thoroughly we cling to routine, even when it’s crumbling around us. Like continuing to use a clearly broken elevator because “it’s only been stuck once this week,” or ignoring a flashing “wet floor” sign because you’re in a hurry, only to perform an unintentional interpretive dance in front of coworkers.

What causes this charming oblivion? Mostly past experience. If nothing bad has ever happened before, then surely nothing ever will. Add in a lack of information, a deep desire not to rearrange your entire worldview, and voilà: denial served warm. This is where cognitive dissonance enters, muttering, “That can’t be right,” every time new information threatens our peaceful little mental picture.

Of course, the real trouble comes when this bias meets actual, life-threatening danger. During World War II, many Parisians couldn’t believe the German army would actually invade. People on the Titanic famously believed the ship was unsinkable, because they were told it was, and it would’ve been rude to question the brochure. In Pompeii, residents continued business as usual while Mount Vesuvius cleared its throat. And then there’s Hurricane Katrina, early COVID denial, and Boeing’s confidence in the 737 Max. Each one is a tragic lesson in why “it’ll probably be fine” is not a risk management strategy.

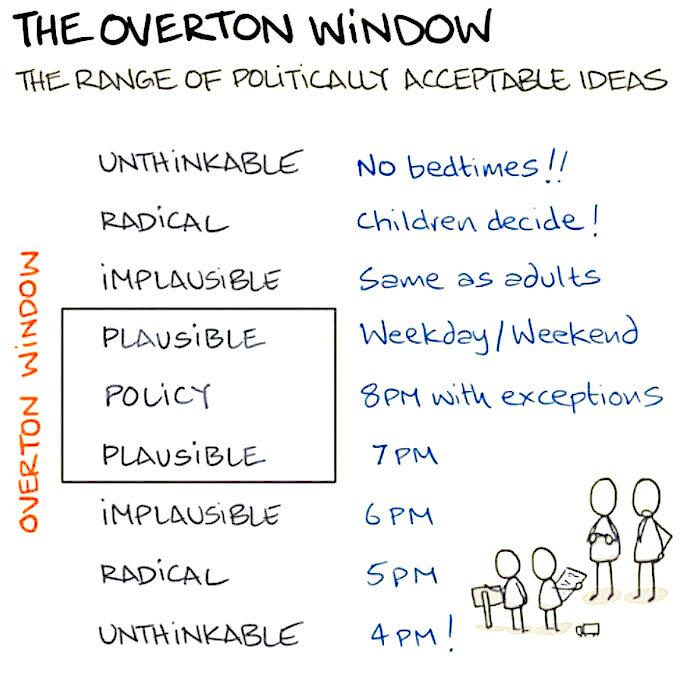

And it doesn’t stop with individuals. Normalcy bias works its magic at the societal level, too. It often teams up with the Overton window, the idea that only a narrow range of ideas is considered “acceptable” at any given time. When the world shifts rapidly, normalcy bias acts as a kind of anchor, preventing people from accepting new realities until they’re smacked in the face by them. That’s why even urgent policy suggestions can sound “radical” right up until they become completely obvious (see: the Internet, remote work, or washing your hands).

The Overton window itself can be unintentionally hilarious. Like when a politician suddenly champions an idea they publicly mocked six months ago, delivering a speech that sounds like they’ve been held hostage by a more progressive version of themselves. Or when someone tries very hard to say all the right buzzwords in the new acceptable range, even if they clearly don’t know what half of them mean. You can practically see the mental buffering.

So why does any of this matter? Because recognizing normalcy bias can actually help you make better decisions, before the lava hits your sandals. In your personal life, it means preparing for things before they’re emergencies, making smarter health and financial choices, and avoiding the “deer in headlights” routine when life throws curveballs. At work, it means facing problems head-on instead of pretending they’ll fix themselves while you reorganize your inbox. Leaders who understand normalcy bias are better equipped to respond to change, adapt in a crisis, and help others do the same, without needing a meteor strike as a wake-up call.

Ultimately, understanding this bias is about ditching the lie of “it can’t happen here” and embracing the much more useful truth: “It could happen, but I’ve got a plan.” Because optimism is great, but denial is not a survival strategy.

Author’s Note:

When I started writing about normalcy bias, I thought, “Surely this won’t take long.” Then I ignored it for three days, convinced I’d just knock it out later. Classic.

If this article made you laugh, squirm, or remember that one time you confidently walked into a glass door, congratulations, you’re human. The trick isn’t to avoid bias completely. It’s to spot it when it shows up wearing a bathrobe and telling you everything’s fine.

Remember: If you ever feel the strong urge to do nothing during a crisis, that’s your brain quietly whispering, “Shh… let’s pretend this is normal.” Politely decline, and get moving.

Leave a Reply